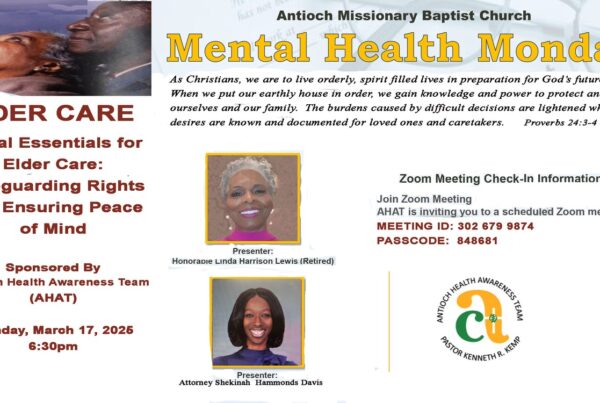

By Jennifer L. Coulter, Attorney-at-law

Updated By Shekinah Hammonds Davis

-

INTRODUCTION

One of the most important and neglected areas of estate planning involves planning for the need for means-tested governmental benefits programs.[1] First the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 and then the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 have resulted in a unified estate, gift, and generation skipping transfer tax credit that means that the vast majority of Americans need not worry about taxation for wealth transfers to their loved ones.[2] At the same time, more Americans are living longer and needing more care and more individuals are being diagnosed with disabilities, shifting the needs of the vast majority of Americans wishing to execute an estate plan. That shift has placed the focus more on long-term care and planning for family members with disabilities than on estate tax avoidance considerations. However, many practitioners still know relatively little about the intricacies of governmental benefits planning.

The lack may, in part, be a result of the exceptionally complex systems involved in governmental benefits planning. Medicaid, for example, is only one possible source of governmental benefits. Others include VA benefits like Aid and Attendance, housing assistance, welfare programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and state and local programs of assistance. Even within the specialized realm of Medicaid planning, though, there are added levels of complications to confuse the issue for the savvy planning attorney. Among those is the simple fact that “Medicaid” is not a single program. It is a series of federally mandated programs administered on a state-by-state basis. Texas alone has between forty-three and forty-five different programs falling under the “Medicaid” umbrella. This variation of number even within a single state relates to the fact that some Medicaid programs, like the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (“PACE”) program,[3] do not operate everywhere in the state, and some of the programs, such as Money Follows the Person have had spotty use, turning on and off as Congress has funded, or failed to fund, them.[4]

Further complicating this matter is the hierarchy of statutes, regulations, and controlling handbooks. The federal statutes, regulations, and handbook explanations are intended to be controlling on all state rules. This means that it should be possible to look to the United States Code (U.S.C.), the Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.), and the Social Security Administration’s Program Operation Manual Systems (P.O.M.S.) and find the rules relevant to the Medicaid programs, and, therefore, to the creation of things such as Medicaid trusts. However, the federal rules provide the most restrictive rules for the Medicaid recipient that are permitted. Each state, within those guidelines, is free to make rules with more liberal policies. Additionally, there is state by state interpretation of many of the federal rules, which results in a number of policy determinations and applications that vary from state to state on issues of significant interest. For example, “trigger trusts” or contingent trusts, which come into existence only upon the happening of an event not necessarily in existence at the time of the drafting of the trust, are permissible in some states, like Texas, but not in other states. Finally, some states have applied to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for 1911 waivers from many of the requirements of the Federal Medicaid laws. CMS has granted many of those waivers, so even relying on the Federal rules as the most restrictive rules may not necessarily be sufficient.

Even with these complications in mind, it is still vital for practitioners, both estate planners, and any other attorney or financial planner, to be able to properly identify the issues surrounding the need for and usage of things like Medicaid trusts. For example, if a family law attorney does not understand the impact of payment of a child support obligation on a disabled child of a divorcing family who might be receiving vital means-tested governmental benefits programs like SSI, CLASS, or Star Plus Plus, the hard fought child support payments may disqualify the disabled child for the programs he or she requires, when the use of a properly established self-settled special needs trust could have retained the benefits. This kind of problem can be especially difficult for programs such as Star Plus Plus or CLASS, which are discretionary spending programs dependent on the legislature to fund them. For those kinds of programs, there may be a years-long wait list, and the accidental disqualification of an individual from such a program may result in years of inability to receive necessary services while the disabled individual works her way back up the wait lists, even if the disqualifying event is corrected immediately.

- GOVERNMENTAL BENEFITS PROGRAMS AND THEIR REQUIREMENTS

Not all governmental benefits programs are created equal, so a practitioner finding that his or her client or a client’s family member has a disability that may require governmental benefits utilization must first determine what benefits the disabled individual is receiving or may be entitled to receive. There are a myriad of governmental benefits programs. These programs have different requirements, some of which depend on the disability and a work history (either of the disabled person or of the disabled person’s parent, grand-parent, or spouse). Some of the programs depend on the disability and means-testing, including income and resources. First then, the attorney must determine which type of benefits the disabled individual is receiving or might be entitled to receive.

- NON-MEANS-TESTED GOVERNMENTAL BENEFITS PROGRAMS

The primary cash benefit program for disabled individuals that is not means-tested is Social Security, received through either Social Security Disability Insurance (“SSDI”) or Retirement, Survivors, and Dependents Income (“RSDI”). This benefit is drawn through either the disabled individual’s own work history[5], or, as is more likely to occur in cases with a disabled individual who has been disabled since birth or since an early age, through a parent’s work history[6]. This form of cash benefit comes with Medicare, a form of health insurance that provides partial coverage (with deductibles, co-payments, and caps on payment) for most medically necessary services, though it does not cover long-term care services.

In order to be entitled to these Social Security benefits, the individual must meet the Social Security Administration’s definition of disability. For a child under the age of eighteen, the definition is that the child has “a medically determinable mental or physical impairment that results in marked and severe functional limitations.” [7]Marked and severe functional limitations exist “when several activities or functions are impaired, or even only one is impaired, as long as the degree of limitation is such as to interfere seriously with the ability to function (based on age-appropriate expectations) independently, appropriately, effectively, and on a sustained basis.” [8] Once the disabled individual reaches the age of 18, the Social Security Administration defines a disability as “The inability of a person to engage in substantial gainful activity due to a medically determinable mental or physical impairment which can reasonably be expected to last twelve months or result in death.”[9] This definition of disability applies to all individuals over the age of eighteen, regardless of the timing of the onset of the disability.

Additionally, for SSDI, the disabled individual must have a sufficient work history himself or herself to have “disability insured status”. There are several sets of rules regarding the work history of the individual to qualify for disability insured status, mostly depending on the age of the individual at the onset of the disability. [10]

Alternately, under certain circumstances, a disabled individual may draw Social Security benefits through the work history of a parent if he or she does not have sufficient work history to qualify through his or her own work history. In order for the disabled individual to draw benefits through his or her parent’s work history, the disabled child must be the child of the person who is “insured” (or entitled to receive RSDI benefits on his or her own work record), dependent on the insured person, unmarried, and have a disability whose onset was prior to age twenty-two. [11]

While RSDI or SSDI are good options for some disabled individuals, their use is limited. For SSDI, the most significant limitation is based on having a sufficient work history. If the individual does not have enough quarters during the relevant time period, then SSDI is simply not a program available to that individual. For RSDI, in addition to the limitation of the timing of the onset of the disability, the insured person, who is the parent of the disabled individual, must already be receiving his or her own RSDI payments on his or her own work record. This means that young parents who are not disabled themselves cannot generally use their own work histories to entitle their disabled children to RSDI payments. That is true even if the cash benefit from RSDI is higher than the cash benefit from SSI.

Neither SSDI nor RSDI is means-tested. The only requirements are disability, work history, and onset of disability in cases of RSDI as discussed above. This means that there are no resource limitations on receipt of these programs. While the programs also have no income limitations for eligibility, income is not entirely without relevance to eligibility. The definition of disability for such programs involves the individual being unable to engage in substantial gainful activity.[12] This means that the individual’s disability renders the individual unable to work. The Social Security Administration determines if the person is able to engage in substantial gainful activity based on a specific dollar amount earned in a given month from employment.[13] In 2022, a non-blind individual may earn $1,350.00/monthly before he or she is deemed to be engaging in substantial gainful activity.[14] A blind individual can earn $2,260.00/monthly before being deemed to be engaging in substantial gainful activity.[15] While this seems to be an income limitation, it is more a component of the definition of disability, and relates only to employment-related earnings.

As an example of the income requirement, it may be useful to examine the various eligibility results if Bill Gates were to become disabled. Should he become disabled, Mr. Gates would be able to receive SSDI based on his work history so long as the disability meant that he was unable to work enough to earn over $1,350.00 monthly. This would be true even if his income from dividends of shares of Microsoft, for example, were well in excess of that amount. This is because SSDI is not means-tested, and income is a concern only to the extent that it affects the definition of disability. In a means-tested program with an income element only, such as Children’s Health Insurance Program (“CHIP”), the income produced from his investments would render Mr. Gates ineligible.

- MEANS-TESTED GOVERNMENTAL BENEFITS PROGRAMS

For many disabled individuals, Supplemental Security Income (“SSI”) is the most common cash benefit to which individuals may be entitled as a result of their disability. SSI provides a cash benefit to any US citizen, Legal Permanent Resident meeting certain requirements, or otherwise entitled alien who is aged, blind, or disabled, and who meets the income and resource limitations of the program. [16] SSI uses the same definitions of disability as RSDI, and the application is likewise made through the Social Security Administration. Unlike RSDI, though, SSI is a means-tested program, which means that there are limitations on the total amount of income and resources that an SSI recipient can have.[17]

In general, the countable resource limitation for a single person is $2,000.00 and for a married person is $3,000.00.[18] These resource limitations have remained unchanged since 1989.[19] While this limit may seem draconian, not all resources are countable. The most common exclusions from countability are the home, one car, an irrevocable pre-need funeral plan, burial plots, certain types of annuities, which must be utilized cautiously, and business property essential to self-support.[20] For a single person, the homestead, provided it is the disabled person’s principal place of residence, is excluded technically without regard to its value, though the “substantial home equity value” doctrine limits the excluded homestead value for a single person requiring institutional or in-home care programs to less than $603,000.00 as a practical matter.[21] There is no dollar limitation on the value of a car, the burial plot itself, or the business property exempted. Additionally, a number of trusts, to be discussed below, are also excluded, regardless of value. As a result of these exclusions, even a single person with a $2,000 countable resource limitation may, in fact, have substantial resources in his or her name provided they fall into one of the excluded resource categories.

Many people try to work around resource limitations by transferring assets to those individuals they wish to benefit upon their passing. However, this is not a practical solution to this problem. Most transfers for less than fair market value during Medicaid receipt or in the three to five years (depending on the program applied for) leading up to Medicaid application will result in a transfer penalty during which the disabled individual is otherwise eligible but is unable to receive benefits while waiting out the transfer penalty period.[22] There are exceptions to the transfer penalty period, including for transfers between spouses, transfers to an adult disabled child, transfers to a trust for the sole benefit of a disabled person under the age of sixty-five, or if there was a solely non-Medicaid purpose. [23] However, the burden of proof that there is an exception to this penalty period is on the Medicaid applicant, as there is a presumption that any transfer for less than full fair market value should trigger a penalty period.

In the context of long-term care Medicaid benefits, the penalty period is determined by dividing the total amount of transferred assets that are transferred for less than full fair market value within the look-back period by the average cost of care in the State. [24] Since the average cost of care in Texas is $237.93 in 2021,[25] a person transferring $2,379.30 without compensation and without the ability to prove that an exception applies will be penalized ten days. This means that the individual will be in an institutional setting like a nursing home, without the income and resources to pay for his or her care, and Medicaid will not pay for that ten-day period. The individual will have to pay privately, despite not having sufficient resources to pay privately.

In an SSI context, the transfer penalty is even more rigid, though the look-back period is, at least, shorter. In that context, the penalty is assessed at $841.00 (2022’s monthly maximum benefit amount) per month[26], so that an SSI recipient who transfers $800 in an uncompensated transfer trigger the loss of benefits for 1 month.

Additionally, an SSI recipient may not have countable income above the total cash benefit amount, which is $841.00 per month in 2022.[27] Most income paid to the disabled person is countable toward this income limitation.[28] However, the income counting rules are complex, and a full discussion of the rules regarding income calculations is beyond the scope of this paper. In illustration of this complexity, one need only consider the treatment of income for a disabled child living with his or her parent. For a disabled child under the age of 18, much, though not all, of the income of a parent who is ineligible for SSI in whose home the child resides is deemed to the child for purposes of counting income to determine the child’s eligibility. [29] This means that, in addition to other items, spousal support paid to the divorcing party who is the custodial parent of a minor disabled child will count, at least in part, toward the income limitation of the child. Once the disabled child reaches the age of 18, his or her parent’s income will no longer count against the disabled child, but there can still be pitfalls. If, for example, the disabled child continues to reside in the home of the parent, the in-kind support and maintenance (the value of the food and shelter provided by the parent) will be counted as income toward the disabled individual’s total income limitations.[30] This harmful effect can be limited, for example by savvy guardianship advocacy, but the rules regarding the mitigation and their intricacies are beyond the scope of this paper.

The SSI rules found in the Code of Federal Regulations Title 20 Part 416, lay out the basic requirements for the Medicaid programs,[31] though the requirements vary from program to program and state-to-state. In Texas, there are between 43-45 different programs that all fall under the umbrella of “Medicaid. All of these programs are means-tested in one way or another.

Probably the most common type is regular Medicaid, which is used as the health insurance of last resort and is what most individuals think of as traditional Medicaid. This type comes with SSI eligibility in Texas, and follows the SSI rules precisely. [32] Texas is a “turn-on” state, meaning that a person who is deemed eligible for SSI simply begins to receive regular Medicaid without any other evaluation by the State for eligibility. [33] However, there are many other Medicaid programs available, and they often have different income limitations and occasionally even varying resource treatment, discussed later in this paper. While a program like CHIP has an income limitation but no resource limitation, most Medicaid programs have both an income and resource limitation. For many Medicaid programs, the resource limitation tracks the SSI resource limitation of $2,000 in countable resources for a single person and $3,000 for a married couple. It is generally, then, the income limitations that vary from program to program. These begin at the SSI limitation of $841.00 per month[34] to the “special income limitation” that applies to long-term care programs, which is $2,523.00 in 2022. [35]

All of these programs cover different types of services in addition to having different limitations. While a full review of the wide variety of Medicaid programs and their requirements is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to know what each program does as well as to know what its limitations are when advising clients. It may not make sense, for example, to put $100,000 into a self-settled special needs trust for a client to make her eligible for Select Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary (“SLMB”), a program that pays the Medicare Part B premiums for a qualified individual when the Medicare Part B premiums are only $135.50 per month in most cases. It may, however, make sense to put the same $100,000 into a self-settled special needs trust if the benefit to be received is something like Medicaid for nursing homes, one of the long-term care Medicaid programs, where the monthly out of pocket costs of ineligibility to the disabled individual may well exceed $7,000.00 per month.

It is regarding these long-term care programs where most of the Medicaid planning in Texas takes place, because the programs have more opportunities for planning. These programs maintain the $2,000.00 resource limitation for a single person but may allow a substantially larger amount to be protected for a married couple. Called spousal impoverishment rules, these are designed to protect the healthy spouse against spending all available community or separate resources on the spouse who needs care, thus draining the funds of the healthy spouse, leaving the spouse in the community unable to support himself or herself without governmental assistance. There are five basic scenarios for a married couple making application for long-term care benefits, and each option allows the protection of a different amount.

In the first type of scenario, there is an institutionalized spouse who requires Medicaid benefits and a community spouse who does not. In this case, the couple’s combined non-resource produced income is above the Maximum Monthly Maintenance Needs Allowance or MMMNA. The MMMNA in 2022 is $3,435.00.[36] This is the amount the state believes that the community spouse needs to have at his or her disposal in order not to be so impoverished that he or she might require governmental benefits himself or herself. In such a case, the amount protectable for the community spouse is called the spousal protected resource Amount (“SPRA”).[37] The SPRA in this case is determined by calculating the total in countable resources as of the assessment date, often called the snapshot date. The assessment date is the first day of the first month in which the institutionalized spouse is under continuous care.[38] The snapshot value is then divided in half. One half is the community spouse’s protectable amount up to the maximum protectable amount of $137,400.00 in 2022.[39] The remaining one half is the institutionalized spouse’s and must be spent down to under the resource limitation for a single person of $2,000.00. There is also a minimum protectable amount that will be protected for a community spouse regardless of what ½ of the value of the total countable resources on the assessment date is. In 2022, this amount is $27,480.00.[40]

This is true regardless of the actual ownership of the assets. The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (“HHSC”) does not care if all assets are the community property or separate property of the spouses. [41]The determination of the community spouse’s protectable amount is made based on the total in countable resources available to either spouse as of the snapshot date, regardless of the character of the assets. [42] This means that in a couple where one spouse has substantial separate property that separate property is still a part of the spousal protected resource assessment, even though it may not belong to the individual making the Medicaid application.

An example of this treatment may be seen where a wife enters a nursing facility on March 15, and her husband remains at home. HHSC will determine the amount the couple had in total countable resources as of March 1. If that amount was $100,000.00, the SPRA would be $50,000.00 for the husband at home. The remaining $50,000 would have to be spent down until she is below the $2,000.00 resource limitation. If, however, the couple had $300,000 in total countable resources on March 1, the SPRA for the husband is $137,400.00 and the protectable amount for the wife is $2,000. The remaining $162,600.00 will have to be spent down to make the couple eligible. If, on the other hand, the couple had $30,000.00 on the assessment date, then the SPRA would be $27,480.00, the institutionalized spouse would receive a $2,000.00 resource limit, and the remaining $520.00 would need to be spent down.

In the second case, there is an institutionalized spouse who needs Medicaid benefits and a community spouse who does not in which the combined non-resource produced monthly income of the couple is below the MMMNA. In such a case, the foregoing SPRA assessment will be completed first. However, if that assessment leaves the institutionalized spouse ineligible, an assessment will be done to determine if the SPRA can be expanded. [43]A SPRA can be expanded enough so that, were all the couple’s countable resources placed in a one year CD, the CD would produce enough in monthly interest that it would bring the combined income up to the MMMNA. [44]

For example, take a case where such a couple had $2,150.50 in combined countable monthly income after allowable deductions. They would need a CD to produce $1,000.00 per month in order to bring their income up to the MMMNA. If one year CDs were paying locally at 1%, HHSC would allow the community spouse to keep the lesser of the total countable resources as of the snapshot date of the couple or $1,200,000.00, the amount required to bring the community spouse’s income up to the MMMNA in a one year CD. Fortunately in the current interest bearing economy, it is not necessary to actually purchase such a one-year CD.

In the last three couple scenarios when making application for long-term care Medicaid benefits, both spouses are institutionalized. If both are institutionalized and both require Medicaid benefits, then there are two possible types of treatment. First, the couple can be treated as a couple with a $3,000.00 resource limit. [45] In Alternately, the spouses may be treated as individuals, allowing each of them a $2,000.00 resource limit and allowing each of them the exempt resources. [46]In the final scenario, the couple are both institutionalized, but only one spouse requires Medicaid. In such a case, only those resources in the name of the spouse making application are counted toward the $2,000.00 resource limitation. [47]Since there are no penalty periods for spouses who make transfers to one another, this situation allows the spouse whose income is insufficient to pay his or her care to simply transfer all assets into the name of the spouse with the greater monthly income, and then make application in the following month. There is no cap on the total countable resources of the non-Medicaid spouse in such a set of circumstances. It does not matter for Medicaid purposes if the property continues to be community property so long as the Medicaid recipient spouse’s name is no longer on the asset, though obviously a Partition of Community Property Agreement should be entered into and the property gifted to the non-Medicaid spouse.

The long-term care Medicaid benefits programs for nursing facility care as well as the 1915C Waiver programs (including the Star Plus Plus program) also have an unusual income requirement. Although they are technically capped at the special income limitation of $2,523.00 in 2022, the income limitation of these programs- but only these specific programs- may be overcome by the use of a Qualified Income Trust, commonly called a Miller’s Trust, which will be discussed later in this paper. [48] This is a feature unique to these programs. Income limitations may not be overcome in this manner in any other program, including in a program like Community Attendant Services (CAS), a Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) program with the same $2,523.00 income limit.[49] Additionally, a hopeful Medicaid recipient cannot simply disclaim any income stream, as any such waiver of income is treated as a transfer of assets subject to a penalty period. [50] This makes long-term care Medicaid programs flexible in a way that most other Medicaid programs simply are not.

III. MEDICAID TRUSTS

It is generally not possible to use standard non-Medicaid trusts in most cases to establish or maintain Medicaid eligibility for an individual because of the treatment of trusts by both the Social Security Administration and each state’s administrative body operating the state’s Medicaid programs. There are three basic ways that those bodies will evaluate any trust for means-tested governmental benefits.[51] First, they will determine if the corpus of the trust is a countable resource to the individual or a person whose resources are deemed to the individual making the Medicaid application. Second, they will determine if any distributions made from the trust are countable income to the individual or to any person whose income is deemed to the individual making application for Medicaid benefits. Finally, they will determine if the transfer to the trust is a transfer subject to a penalty period under the look-back provisions of 42 U.S.C. Section 1396(P)(c).

Revocable trusts created by the individual or the individual’s spouse, who is treated as the individual for these purposes[52] will be treated as fully countable to the individual. [53] This means that the entire corpus of a revocable trust of which the individual is a grantor will be countable toward the individual’s total countable resource limitation. This countability in Texas and a number of other states includes the homestead of the individual where the home is held in a revocable trust, although it would be exempt from countability if held outside the trust.[54] Finally, any distributions to any individual other than the disabled individual or his or her spouse will, of course, be treated as a transfer of assets subject to the usual penalty periods.[55]

Irrevocable trusts receive somewhat different treatment in regards to resource counting, but if there are any circumstances under which the individual has the legal right to receive part or all of the corpus of the trust, the portion the individual can access will be considered countable to the individual.[56] Additionally, any distributions to the individual and some distributions for the benefit of the individual are treated as income.[57] To the extent that the individual cannot access the corpus of the trust, a transfer to an irrevocable trust that is not one of the Medicaid acceptable trusts discussed below is treated as a transfer subject to the usual transfer of asset rules.[58] If some portion of the trust becomes inaccessible to the individual only at a later time after the establishment of the trust, it will be treated as countable, generally putting the individual above the $2,000.00 resource limit, until dispersal to the individual is foreclosed. That foreclosure will be subject to transfer of assets penalties, making the individual unable to receive benefits once eligible for them while waiting out the transfer penalty.[59]

As a result of these harsh treatments on trusts created by the individual, the usual trusts are not a good idea for an individual who may need Medicaid benefits. In fact, it may be that the creation of revocable trusts may be detrimental as they are so commonly used for individuals with modest estates who do not yet need Medicaid benefits but who may require future means-tested governmental benefits programs. Frequently, the result of the creation of such trusts is that they are funded with little more than the individual’s homestead, which means that the individual has converted his or her largest protectable resource into a countable resource should the need for Medicaid benefits arise, often costing the individual months’ worth of eligibility and occasionally resulting in the individual selling his or her homestead to pay for nursing care rather than taking advantage of the exemption available to him or her.

The alternative, then, is to carefully assess the situation and properly use one of the Medicaid trusts. Some of these are statutory creations, and some are developments of the common law. Their treatment may vary from state to state, so it is important in drafting such trusts to understand the complexities and ensure that the best language is being used. The next sections of this paper will discuss the various types of trust that are commonly referred to as Medicaid trusts and the situations in which each may be utilized.

- SELF-SETTLED SPECIAL NEEDS TRUSTS

One solution to the problems faced when an individual has resources that disqualify her from means-tested governmental benefits programs otherwise needed is to create a self-settled special needs trust. Self-settled special needs trusts are the kind of trusts that are often thought of when people refer to Medicaid trusts. These trusts are statutory creations provided for in 42 U.S.C § 1396 (P)(d)(4)(a), and are often referred to as D4A trusts or first-party special needs trusts. Self-settled special needs trusts can be useful devices for obtaining or maintaining eligibility for a disabled person when the disabled person herself has resources that disqualify her from the receipt of means-tested governmental benefits programs.

In order for a trust to qualify as a Self-Settled Special Needs Trust, it must meet several requirements.

First, the individual for whom the trust is being created must be under the age of sixty-five at the time of creation of the trust.[60] Some states are more liberal regarding this element, but Texas is not among them. A self-settled special needs trust in Texas must be established before the disabled person’s sixty-fifth birthday. [61] Additionally, while the trust will remain exempt after the person’s sixty-fifth birthday as long as the individual himself or herself remains disabled, in Texas, any additions made to the trust of the individual’s resources after the disabled individual’s sixty-fifth birthday are treated as transfers of assets subject to penalty periods.[62]

Second, the individual creating the trust must be disabled pursuant to the Social Security definition of disability as discussed above at the time of the creation of the trust.[63] This restriction means that an otherwise healthy individual approaching her sixty-fifth birthday cannot establish such a trust to protect her savings from countability should the need arise for long-term care Medicaid benefits at some later date. It is not necessary for the individual to be receiving any disability benefits at the time of the creation of the trust, but the disability itself must exist at the time of the creation of the trust. If the person is disabled but does not yet have a disability determination, it may be desirable to begin the process for receiving the disability determination contemporaneously with the creation of the trust, especially for a disability that is not triggered by a single event to prevent later questioning of the existence of the disability at the time of the creation of the trust.

Third, the trust must be created by the disabled person, his or her parent, grandparent, guardian, or a Court. [64]While these are referred to as “self-settled” or First-party settled” trusts, it isn’t actually necessary for the disabled person himself or herself to actually establish the trust. The disabled person must be the sole beneficiary, but need not actually be the grantor of the trust. In fact, until 2016, it was impossible under the rules for the disabled person herself to create the trust under the statute, even if the disabled person’s disability was strictly physical. The passage of the Special Needs Trust Fairness Act allowed the disabled person to create the trust, but he or she is still only one of the possible people who may do so.[65]

Fourth, the trust must have a Medicaid pay-back provision.[66] This provision must provide for the repayment to any State in which the Medicaid recipient has received Medicaid benefits.[67] This repayment provision may allow for costs of administration to be paid prior to the State being repaid, but no other expenses may be paid first, including the disabled person’s funeral expenses.[68] Repayment must be made upon any event of termination of the trust. [69]Generally, this is done when the disabled person dies, but where earlier termination is possible, repayment must be made before the death of the beneficiary. This repayment must be for all benefits for medical assistance paid out under any State plan to the full extent of the benefits received. [70] However, the repayment does not include for any means-tested cash benefit the beneficiary received, such as his or her SSI payment, if any. Only after such repayment can the disabled individual’s heirs receive any portion of the trust corpus.

Fifth, the trust must be for the sole benefit of the disabled person.[71] While the statute requires only that the trust be “established for the benefit of the individual,” both the Code of Federal Regulations and the POMS have taken a more stringent approach, requiring that all distributions be “for the sole benefit of the individual.” [72] This “sole benefit rule” is strictly interpreted by the Social Security Administration, and any trustee of a Self-Settled Special Needs Trust should be conscientious about the administration of the trust to prevent inadvertent disqualification of the beneficiary for failure to comply with the sole benefit rule. Even some distributions that would seem to be for the sole benefit of the disabled individual have been treated as impermissible distributions that can render the entire trust subject to the rules that apply to most trusts established by an individual, though the SSA has relaxed its standards regarding sole benefit somewhat in the most recent update to the Program Operation Manual Systems (POMS). In the past, a pool put in for therapeutic uses for the disabled person could render the trust countable if any other family members swam in it. Now, the SSA has determined to overlook other individuals’ incidental benefit from distributions. The SSA has also relaxed its prior restriction on payment of travel companions from such trusts, so long as the travel companion is medically necessary.

Sixth, the trust must be irrevocable. [73]If the disabled person has the right to revoke the trust, then he or she has the legal right to access the assets. That is the definition of what an available, and generally a countable, resource is.

Seventh, the disabled person cannot be the trustee of such a trust. Generally, this is because it gives the disabled person too much access to the trust. This will be true of each of the types of trusts discussed in this paper.

These types of trusts must also be funded with assets belonging to the disabled person. [74]These funds may come from any source, such as an inheritance, personal injury settlement fund, or child support paid to the disabled person. The key element is that the funds belong to the disabled person herself. It is not impermissible to place assets belonging to a third party into such a trust as well, but it is strongly inadvisable. This is because both the pay-back provision and the limited distribution standard discussed above make self-settled special needs trusts one of the most restrictive of the Medicaid trust types. Generally, then, if a third-party has assets he or she wants to give to a disabled person, those funds should not be comingled into a self-settled special needs trust but rather put into a separate third-party settled special needs trust, to be discussed below.

Many people use extremely restrictive language in the grant of authority for distributions, including the “supplement, but not supplant governmental benefits” language, but these restrictions are, often, more restrictive than required, so less restrictive language such as “for the sole benefit of” may be used instead.

Despite the above limitations, a self-settled special needs trust is useful where the disabled person has resources that would disqualify her for means-tested governmental benefits. This often happens when the disabled person had resources that would disqualify her from benefits before becoming disabled, but may also occur when the disabled person receives a sum that would disqualify her from receipt of benefits, such as from a settlement of a personal injury lawsuit or from an inheritance from a parent who did not plan for the disability of the child. In these cases, it may be useful to create a self-settled special needs trust.

However, the restrictions on use of the trust, on who may establish a self-settled special needs trust, and the pay-back provisions, are such that it is often better to find alternate spenddown items and to advise the family members of disabled individuals to plan in advance for the creation of third-party settled special needs trusts, where possible. For example, a disabled individual who receives a $100,000.00 inheritance outright will generally be disqualified from the receipt of means-tested governmental benefits while she has the outright right to access the inheritance. It may be possible for such a person to create a self-settled special needs trust, provided she is under sixty-five at the time she inherits the funds, and for many that may be the correct course of action. There can be barriers to creation of such a trust, though. If the disabled individual does not have a parent or grandparent living and able to establish the trust for her and she has more than a physical disability, resort must be had to the court to establish it. This is both costly and time-consuming, and during all the months in which court proceedings are pending, the disabled person continues to be ineligible for the needed benefits. In a case where the disabled individual has very high monthly costs, such as in the case of many quadriplegics or for individuals on wait lists for organ transplants, it may be possible to largely deplete these funds before a self-settled special needs trust can be properly established by the court. It may also be inappropriate for an individual because of the limited distribution standards or because the likelihood is that the disabled person will not use the funds during lifetime if her monthly income, in combination with her Medicaid benefits, is sufficient for her daily needs.

In such cases, it may be advisable instead to determine if the disabled person has the usual exempt items. If the disabled person does not own her own home, for example, she may want to purchase a home that will be exempt, and which she can pass, free from the Medicaid pay-back provisions of a self-settled special needs trust and free from the Texas Medicaid Estate Recovery Program through a revocable transfer on death deed or Lady Bird deed to her chosen beneficiaries.[75] It should also be evaluated whether the disabled beneficiary has the other common exempt items, such as her own car (if appropriate), or has pre-paid her funeral expenses through a device like a pre-need funeral plan or a funeral expense trust. This latter item is especially important since, as mentioned above, there is no requirement that funeral expenses be paid before recovery.

- POOLED TRUSTS

The legislature has also allowed for the creation of pooled trusts. These trusts allow the assets of a disabled person to be placed into a pooled trust with other disabled individuals to be managed by a non-profit organization, such as the Arc of Texas.[76] These trusts, called master-pooled trusts or D4C trusts, are similar to D4A self-settled special needs trusts in that they allow a disabled individual with resources disqualifying her from the receipt of means-tested governmental benefits programs to transfer assets into the trust and have them not counted for purposes of qualifying for those programs. Pooled trusts can be used to solve some of the problems associated with self-settled special needs trusts.

In order for a trust to be an appropriate pooled trust for D4C purposes, it must meet certain requirements. First, it must be established and managed by a non-profit organization.[77] In pooled trusts, the trust itself is created by the nonprofit organization, and each new disabled individual utilizing the trust signs a joinder agreement. Second, as with a self-settled special needs trust, the individual must meet the Social Security definition of disability.[78] The individual, as well as the individual’s parent, grandparent, guardian, or court maysign the joinder agreement and essentially create the sub-account.[79] Additionally, pooled trusts must keep separate accounts for each disabled individual but pool funds for the purposes of investment and management.[80] As with D4A self-settled special needs trusts, pooled trusts must also be maintained for the sole benefit of the disabled individuals.[81] Additionally, pooled trusts need not necessarily pay the State, but the alternative is not that the corpus of the disabled individual’s separate trust is paid to the individuals the disabled person might otherwise choose. The options are payment to the State or retention of the corpus by the pooled trust. [82]

While pooled trusts suffer from many of the same limitations as self-settled special needs trusts, including the problem of the limited distribution standard and pay-back provisions, they can overcome many of the difficulties associated with the D4A trusts. Because the trusts are managed by trustees who handle many trust accounts for the benefit of disabled beneficiaries, there is less risk that distributions will be made from the trust in a manner that might inadvertently disqualify the individual from the very means-tested governmental benefits programs it is established to protect. However, administration of pooled trusts can be costly whereas a self-settled special needs trust administered by a parent or other family member can be less costly when the administrator is willing and able to administer such an account at no cost to the disabled individual. It should be noted that one provision explicit in a D4A trust- the requirement that the individual be under 65 at the time of the establishment of the trust- is not a part of the requirements for a D4C Pooled trust.[83] However, while this is not a Federal requirement, Texas (and a number of other States) imposes a transfer penalty for transfers to such trusts after age 65, effectively imposing an age requirement in pooled trusts for most people. [84]Whether a D4A or a D4C trust is elected, though, these types of exception trusts provide a good option for many disabled individuals in need of means-tested governmental benefits programs from which their resources would otherwise disqualify them.

- THIRD-PARTY SETTLED SPECIAL NEEDS TRUSTS

A far preferable option than a self-settled special needs trust or a pooled trust is for a disabled individual simply not to receive resources of her own that might disqualify her from the receipt of means-tested governmental benefits programs. While there is nothing that can be done to prevent the individual from receiving a personal injury settlement or child support payment that might cause disqualification [85], in cases where resources causing disqualification may come from a family member or friend, such as by intervivos gift or through inheritance, steps may be taken to find better outcomes. A common practice, unfortunate as it is, is to advise families with disabled members simply to write out those family members for fear of causing disqualification. This is an unnecessary practice, and one that quite frequently results in a thwarting of the family goals, harm to the most vulnerable family members, and benefit to those who often need it least. A better option if the family wishes to protect and provide for their disabled family member is to propose a third-party settled special needs trust.

Third-party Settled Special Needs Trusts are non-statutory common-law creations, as compared to the statutorily-created Self-settled Special Needs Trusts. There is no specific language or form to be used. [86]However, there are common drafting considerations and techniques which can be employed to ensure that the trust will be an excluded resource to an individual needing means-tested governmental benefits. Keeping these in mind can assist a careful practitioner in creating Special Needs Trusts that can be flexible enough to meet changing circumstances while ensuring maximum protection from countability.

The first consideration is the source from which the funding of the trust is derived. No part of the assets held in a Third-party Settled Special Needs Trust can belong to the disabled individual. [87] Any contribution to the trust by the disabled individual is sufficient to convert the trust from a Third-party Settled to an attempted Self-settled Special Needs Trust with all the complications that entails. Among the complications is that a Self-Settled Special Needs Trust has limitations as discussed above that a Third-Party Settled Special Needs Trust does not, meaning that the trust, if a properly drafted Third-Party Settled Special Needs Trust is likely to fail as a Self-Settled Special Needs Trust. If the individual adding those resources is over sixty-five and unable to benefit from a Self-settled Special Needs Trust, transfers to such trust may result in either inclusion of the corpus of the trust or in a transfer penalty for the transfer to the trust.[88] It is useful then, when drafting and funding the trust to ensure the actual ownership of the resources and to specifically prohibit the Trustee from accepting any funds belonging to the disabled individual, whether offered by the disabled individual him or herself or by another on behalf of the disabled individual. An outright inheritance, even where a court may establish a special needs trust for the benefit of the disabled individual, unless such trust is created by the Court in response to a Petition to Reform a Will pursuant to Texas Estates Code Sec. 255.451, will count as the individuals’ money in this context.

The trust must also be discretionary, meaning sole discretion as to all distributions lies with the Trustee. [89] The disabled individual should not be able to demand or compel distributions. There is some argument to be made that, even where the distribution standard is “sole, absolute and unfettered discretion of the Trustee” that the beneficiary can bring an action in court to enforce some distribution. However, this simple ability, unlike the ability to compel distributions where the Trustee “shall make distributions,” is disregarded for the purposes of determining the countable nature of the trust in Texas. In a discretionary trust, the disabled beneficiary does not have sufficient control over the trust estate to trigger countability.[90] The use of the “sole benefit” language in such trusts is not necessary. There is no requirement in a third-party settled special needs trust that the disabled beneficiary be the only permissible distributee. Distributions may be made for the benefit of any individual the grantor desires without fear of either creating inclusion in the disabled individual’s total countable resources or in triggering a transfer penalty since the funds never belonged to the individual in the first place. However, if such a trust is to receive a gift to or for the benefit of a disabled individual which the giftor wishes to exempt from transfer penalties assessed against himself, the trust must be for the sole benefit of the disabled beneficiary.[91]

The disabled beneficiary may not be the Trustee and should not have the ability to be named Trustee while she is still a disabled individual receiving or anticipating receipt of governmental benefits. [92] The same reasoning applies as to why the disabled beneficiary cannot be allowed to compel distributions, though more forcefully here; as Trustee, the disabled individual would exercise enough control over the trust estate to make it a countable resource. Provision may be made in Texas for naming the disabled beneficiary as Trustee in the event that she is no longer disabled and receiving or anticipating receipt of governmental benefits. However, interpretations may vary from state to state. It is useful to include a savings clause to any such power. As such, the language that might be used in such a case might, though need not necessarily, read as follows:

In the event that John Doe, for whom this trust has been established, is no longer disabled as that term is defined in 42 U.S.C. §1382(c)(4) and is no longer receiving or anticipating the receipt of any means-tested governmental benefits or assistance program, John Doe may be appointed to serve as trustee of this trust, provided, however, that if the existence of this power, whether or not exercised, creates ineligibility for any such means-tested governmental benefits or assistance program, the foregoing power shall be null and void.

Finally, while it is not a requirement, it is often helpful to state the purpose of the trust and provide a non-exhaustive list of permissible distributions as guidance. This statement of purpose can be broad, such as:

The purpose of the John Doe Special Needs Trust is to provide for the support of John Doe as liberally as will not disqualify him from receipt of any governmental benefits or assistance program to which he might be entitled, unless the Trustee of this trust and John Doe determine that such disqualification is in John Doe’s best interests. Distributions to or for the benefit of John Doe to meet such purpose may include, but are not limited to, housing, food, travel, clothing, educational expenses, travel expenses, and otherwise not covered medical expenses.

This expression of purpose should include a savings clause to limit or entirely nullify the Trustee’s ability to disqualify the disabled individual from the receipt of governmental benefits if the existence of the power is sufficient to cause the disqualification.

Provided that these requirements are met, a third-party settled special needs trust has much better treatment than any trust established by the individual. It is entirely non-countable for Medicaid purposes. [93] Creation of the trust is not a transfer of assets, regardless of the disabled person’s age, since the disabled person never had the right to the assets. [94]Distributions to or on behalf of the disabled beneficiary will be treated under the usual income rules any disabled person faces. [95] So long as payments are not made for “in-kind support and maintenance” or ISM, which are for food and shelter, as the POMS defines it, or if such ISM distributions are made in the context of long-term care Medicaid benefits, which does not count ISMs as income, then a pragmatic trustee can avoid making any distributions to the beneficiary that might be considered income.[96] As a final benefit, there is no Medicaid payback provision required, although it should be observed that it is vital not to place a payback provision in a trust that does not require one, as the terms of the trust itself will prevail. The state will be repaid if the provision is included-whether it is necessary or not.

- TESTAMENTARY TRUSTS

While as a general rule most third-party settled special needs trusts can be created through intervivos trusts[97], there are some cases where that is not possible. The statutes defining the undesirable treatment of all trusts established by an individual that make most usual trust planning impractical from a governmental benefits standpoint specifically define the individual to include her spouse unless created by will.[98] As a result, the creation of an intervivos trust for the benefit of a spouse, even if it is fully funded with assets not belonging to the disabled spouse and of which the disabled spouse has no ability to compel distributions is treated exactly as though the disabled person herself created the trust with her own funds. It receives the same harsh resource, income, and transfer treatment as does a self-settled non-special needs trust.

The caveat to that treatment, though, is to be found in the simple expression “other than by will”. The code’s provision for when the spouse is treated as the individual reads: when she creates a trust for the benefit of a disabled spouse “other than by will”. [99] As a result, it is common practice to create testamentary third-party settled special needs trusts for the benefit of a disabled spouse, or, given the broad discretionary language permitted for distributions, for any spouse where it may be desirable to protect some resources for the surviving spouse in case of later need for means-tested governmental benefits programs such as may happen if there is a need for a nursing facility placement longer than the one hundred days for which Medicare may pay. It should be remembered, though, that the trust itself must be testamentary. A pour-over will into an intervivos trust created by the spouses is not sufficient.

As with any third-party settled special needs trust, a testamentary Medicaid trust should not appoint the survivor as Trustee of the trust and must allow absolute discretion in the Trustee for all distributions from the trust.[100] Although “supplement but not supplant” language is often used in these types of trusts as well as in other third-party settled special needs trusts, it is not necessary for Texas Medicaid benefits and can unnecessarily restrict the ability of the Trustee to make distributions to or on behalf of the beneficiary. A simple support trust with sole discretion in the Trustee is sufficient at this time.[101] However, the careful planner, knowing that people may move into other jurisdictions and that statutes and regulations change over time, can provide for the broadest language possible with a type of savings clause restricting distributions from the trust if the inclusion of the broader support language itself causes disqualification from benefits. The language may appear as follows in the Will of the spouses:

To my son, as Trustee of the Medicaid Testamentary Trust for the benefit of my wife created herein. The Trustee shall have the sole, absolute and unfettered discretion to make distributions to or on behalf of my wife for her support. However, if the mere existence of the previous power causes disqualification for any governmental benefits or assistance programs to which my wife might otherwise be entitled, the previous sentence shall have no affect and the Trustee shall have only the power to make such distributions as will not cause disqualification.

Once the wills creating the Medicaid Testamentary Trust are in place, it is essential to ensure that the planning is completed on the practical level. Many good estate plans are undone by virtue of clients engaging in accidental or inadvertent estate planning. The planner must also ensure, in this case, that the assets of both parties pass to the estate or to the trust created in the will and not by some alternate non-probate distribution scheme outright to the surviving spouse. This is common where there are retirement plans, life insurance policies, or joint bank accounts, on which many people simply name their spouse as beneficiary when they initially complete the forms and which are never later reviewed. Without this step on the part of the good estate planner, it is possible for the trust to contain nothing but the already exempt homestead and for the rest to pass unprotected to the surviving spouse by beneficiary designations and right of survivorship agreements.[102]

Another step to consider in planning for the death of one spouse is partition of community property into separate property pursuant to Texas Family Code § 4.102. While Medicaid does not consider the separate or community property character of assets when determining initial Medicaid eligibility[103], only assets which pass pursuant to the Will into the Testamentary trust will be excluded from countability to the surviving spouse. If all assets of the couple are community property, only half may be protected upon the death of the first spouse to die. Where we have a seriously ill spouse likely to predecease a relatively healthy spouse or a spouse already on Medicaid and a spouse at home where the assets must be transferred out of the name of the Medicaid spouse within the first year of eligibility,[104] an agreement to partition the community property and a gift of the Medicaid spouse’s interest in his or her separate property can ensure that the maximum amount is protected from Medicaid countability for the survivor.

Protecting these resources in a Medicaid Testamentary trust can allow the surviving spouse to stretch the life of the assets by permitting her to receive Medicaid benefits to offset the cost of long-term care, either at a nursing facility or in home, while avoiding many of the problems associated with a single person’s receipt of benefits in a means-tested program. Many single individuals who receive benefits in a skilled nursing facility have difficulty maintaining their exempt homesteads. With only $2,000 in countable resources and nearly all monthly income going to the facility, paying for homeowner’s insurance, property taxes, and routine maintenance can be problematic unless the individual qualifies for the home maintenance diversion,[105] which is not common. Additionally, many Medicaid recipients have personal needs expenses that exceed the $60 allowance presently allowed under Medicaid rules.[106] They may need care above and beyond the care Medicaid can provide, especially if the individual remains at home where Medicaid in Texas cannot provide 24-hour a day care. All of these expenses can, with care, be paid out of the trust resources without disqualifying the Medicaid recipient from benefits.[107]

- QUALIFIED INCOME TRUSTS

While they neatly fall into the category of “Medicaid trusts”, as they are useful only to correct a Medicaid eligibility problem, qualified income trusts, also called “Miller’s Trusts”, do not serve the same purposes as any of the above trusts. Qualified income trusts can never be used to fix a resource problem or to protect resources from countability. Qualified income trusts are used solely to allow a disabled individual with income in excess of the income limitation to become eligible for certain long-term care Medicaid programs such as for nursing facility care or the 1915C waiver programs.[108]

In order for a trust to be a qualified income trust, it must meet certain requirements, including how and when distributions are to be made. Operated improperly, qualified income trusts will cause disqualification for the individual. First, then, the trust may be established by anyone pursuant to the statute [109], though in practice, it should be established by someone with the ability to access the disabled individual’s income, such as a guardian, agent under durable power of attorney, Social Security rep-payee, or the individual himself or herself. Second, the corpus of the trust must be comprised exclusively of the disabled individual’s income.[110] Third, the state in which the disabled individual resides must be one that is providing and failing to provide, specific kinds of Medicaid benefits to individuals.[111] Texas is one of these states. Fourth, all income from any source used to fund the QIT must be placed into the QIT. This requirement means that if the individual requiring the QIT receives $1,001.00 in social security each month but deposits only $1,000.00 into the QIT, it is not a properly administered QIT and will not allow income eligibility in that month. Fifth, the income deposited into a QIT must be deposited into the trust in the same calendar month as the month of receipt.[112] Since the income of a trust should be paid out each month for approved expenses, there should be only a small amount in a QIT at any time. However, the total amount in a QIT at the death of the Medicaid recipient must be paid to the State dollar for dollar for all medical assistance paid out on behalf of the Medicaid recipient during life. [113]Finally, the trust must be irrevocable.[114]

Texas is one of the states that require qualified income trusts for individuals with income in excess of the special income limit.[115] In 2022, the special income limit is $2,523.00,[116] so any individuals with gross income in excess of that amount in 2022 will require a qualified income trust in order to become eligible for the long-term care programs. It is also important to note that the income used for determining the individual’s eligibility for such program is the disabled individual’s income only. It is not the income of the individual’s spouse.[117] If the individual has $1,000.00 per month in income, he or she is eligible for these types of benefits programs even if his or her spouse has $5,000.00 a month or more in income.[118] Qualified income trusts, though, should be used for no other Medicaid purposes, and most states do not require them to overcome the special income limitation. Additionally, since they can be utilized only to overcome the special income limit in certain types of programs, in order to correctly utilize a QIT, it is vital to fully understand the program the client might need.[119]

- MISCELLANEOUS TOPICS

- CONTINGENT TRUSTS

Many estate planning clients do not have these specific governmental-benefits concerns when contemplating their estate plan. Their children and spouses are healthy. Frequently then, it may seem excessive and unnecessarily restrictive to create trusts for their beneficiaries, especially if the beneficiaries are not to be the Trustees of those trusts. Many people will want to give the gift outright. However, most probate attorneys can give story after story of beneficiaries whose health or situation altered before the death of the individual creating the will. In these scenarios, contingent trusts can be life-saving (and asset protecting) tools.

A will or a trust can and should contain contingent trusts for the benefit of any beneficiary who, at the time of distribution, meets any number of criteria. Minor beneficiaries, for example, are perfect for contingent trusts, which come into being only if the beneficiary is under the age of majority (or 21, 25, or any other age depending on client preference) at the time of distribution. The same may be said of people who are under the protection of the bankruptcy courts. Why not also plan for unexpected disability?

Each will and trust may contain a trust that will come into existence only if the beneficiary is: 1) Disabled and receiving or anticipating receipt of governmental benefits which outright distribution would disqualify the beneficiary from receiving; 2) A person whose resources are deemed to a person who is receiving or anticipating receipt of governmental benefits which outright distribution would disqualify the person to whom the beneficiary’s resources are deemed from receiving; or 3) Any other circumstance for which outright distribution may be disadvantageous, a listing of which will be included below.

These contingent trusts can use the same language as a traditional Third-party Settled Special Needs Trust, including the broad grants of power and the same savings clauses to limit those broad grants of power if their existence is sufficient to cause disqualification.

The provisions creating the contingent trusts should also include limitations on the ability to be named executor or Trustee to anyone who is prohibited from outright distribution on the basis of a disability triggering the creation of such a trust. Such contingent trust language may read as follows:

In the event that any beneficiary of this Will has not reached the age of eighteen (18 years of age) at the time of distribution; is disabled and receiving or expected to be receiving State or Federal benefits which outright distribution of any gifts made in this Will would disqualify the beneficiary from receiving, or is a person whose resources are deemed to a person who is receiving or expects to be receiving state or federal benefits which outright distribution of any gifts made in this Will would disqualify the person to whom the resources would be deemed from receiving; is incapacitated as that term is defined in the Texas Estates Code; is under, or has made application for, the protection of the Bankruptcy laws of the United States; is in divorce proceedings; or is incarcerated by either a state government or the federal government at the time such beneficiary would otherwise be entitled to a distribution, then the Executor named in this Will shall establish a Trust for such beneficiary, for the uses and purposes hereinafter set forth to be held and administered by the Trustee named in this Will.

The Trustee, in the Trustee’s sole discretion, shall distribute to or for the benefit of each beneficiary, as much of the income, and in addition, so much of the corpus of each separate, per stirpes share or trust created for that particular beneficiary as the Trustee shall consider necessary or advisable for his or her health, support, education, and maintenance. Where the share is being held in trust as a result of the receipt or anticipated receipt of governmental benefits, if the language of the foregoing clause causes the loss of such benefits for the disabled beneficiary, the Trustee shall have only the discretion to make distributions so defined by the benefit plan as will not disqualify the beneficiary, unless the Trustee and the disabled beneficiary or the disabled beneficiary’s parent, guardian, or other legal representative determines that it is in the best interests of the disabled beneficiary to receive his or her share outright despite potential disqualification from benefits, unless this clause alone is sufficient to cause disqualification, in which case, this clause shall have no legal effect.

Under all instances where a trust is created pursuant to the terms of this Will, the Trustee may distribute the principal and income outright to the beneficiary upon the beneficiary’s attaining the age of majority; the removal of the disability, unless such distribution shall trigger repayment to a state or federal program; the beneficiary’s regaining capacity; or written proof provided to the Trustee showing that the beneficiary has been discharged from the Bankruptcy Court.

No Executor named in this Will, Personal Representative appointed by the Court, or individual making application to the Court for appointment as Personal Representative of this Estate, or Trustee named or serving in that capacity for any Trust created in this Will shall qualify or continue to serve if such individual would be prohibited from outright distribution on the basis of any of the foregoing provisions. Any individual so barred from qualification or continued service as Personal Representative or Trustee may qualify and serve once such impediment is removed.

Any Personal Representative appointed by a Court of competent jurisdiction may, in that Personal Representative’s discretion, create a trust for the benefit of any beneficiary named under this Will whose circumstances are such that the creation of such a trust would be in the best interests of that beneficiary despite the failure of the beneficiary to have circumstances which qualify that beneficiary for the mandatory creation of a trust as provided for above. In the event that the beneficiary does not believe that such a trust serves his or her best interests, such a beneficiary may make application to the Court of competent jurisdiction to have such trust removed and distribution made outright to such beneficiary.

Of course, it must be remembered when creating these contingent trusts that not every state will honor a contingent trust, sometimes called a trigger trust, for a disabled individual. Because of this, it is not sufficient to simply include such contingent trust language in the will (or intervivos trust) of a client where there is a known beneficiary who is disabled and receiving or anticipating the future need for means-tested governmental benefits programs. In such cases, even if the disabled person lives in a state where such contingent trusts are acceptable at the time of the creation of the will, a third-party settled special needs trust should be created outright in the will or trust of the client immediately. It is not possible to know on the date of the creation of the will either where the disabled beneficiary might be living at the time the will is actually implemented or if the state in which the disabled beneficiary presently resides will continue to honor contingent trusts. Despite this concern, the inclusion of contingent trust language in every will and trust leaving an estate planner’s office will ensure that, to the greatest extent possible while still accommodating the realities of individuals’ situations, the will or trust will meet the individual’s goals at the time of its usage rather than at the time of its creation.

- SEE-THROUGH TRUSTS BEFORE THE SECURE ACT

The issue of inadvertent estate planning broached earlier in this paper is one that often causes problems in any kind of estate planning. However, the problem is more serious in the arena of special needs trusts planning. It is not uncommon to see a well-drafted testamentary special needs trust that contains nothing but the house and car, since everything else tends to pass outside of the probate process through beneficiary designations, often passing outright to the individual requiring the special needs trust. Good practitioners will discuss this issue with their clients when establishing trusts, whether for means-tested governmental benefits purposes or not, and that can usually correct the problem. The trust should be named as the beneficiary of the life insurance policies. Beneficiary designations are removed from the bank accounts.

Unfortunately, many good planners have looked at this problem and fixed it for almost, but not quite, every asset. The struggle comes when the asset is the I.R.A., or other Qualified Retirement Plan (QRP). What most casual practitioners know about beneficiary designations in relation to those QRPs is limited to: For the love of not getting sued for malpractice, please, don’t name the estate or a trust- name a person! This, of course, leaves what is often one of the largest assets outside of the home subject to the whims of named individuals and takes it entirely out of the estate-planning framework for reasons that are largely misunderstood.

It is essential, then, to understand first why we are so reluctant to name the estate. When an owner of a QRP dies before having fully distributed the amounts in his or her plan, the remainder of the QRP is subject to a series of complex rules regarding distributions that can have huge implications for income tax purposes. When naming an estate, the entire amount remaining in the QRP upon the death of the original owner must be distributed outright, with all the tax implications of that statement, no later than December 31 of the fifth year following the death of the original owner.[120]

Consider a 72 year old woman with a $1,000,000.00 plan naming the estate at her death, and with a will naming her 35 year old son. The estate must make distribution of the entire amount within five years after the year of death, all of which would be ordinary income. Even if spread out over those available years, the distributions may put the beneficiary into the highest possible tax bracket.

By contrast, if the same QRP owner had simply named her thirty-five year old son to inherit the QRP as her designated beneficiary (a term of art in the Internal Revenue Code that will be discussed later in this paper), before the Secure Act, he could have used his own life expectancy to establish new required minimum distributions (RMDs).[121]In that case, the RMDs may have been spread over the 43 years of life expectancy for the son,[122] rather than over the mere five years required when naming the estate. This meant that in the first year after the death of his mother, the son could take less than $25,000 in RMD, which would count as ordinary income in his annual tax returns. The son could, if he chose, also take more than the RMD, up to and including, the entire amount in the QRP, just as his mother, the original QRP owner could.[123] The ability to “stretch” the QRP over his life expectancy was an election rather than a mandatory rule, but he could gain great tax benefits in this case with an exercise of restraint in making such an election.

However, this changed after the enactment of the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement Act of 2019, also known as the SECURE ACT, became law on December 20, 2019.[124] With this same example, if the 72 year old named her 35 year old son who did not have a disability and who was not chronically ill, the son would have ten (10) years to take full distribution of this account following the year of the owner’s death. However, if the 35 year old son was disabled or chronically ill, then the distribution period would be based on the life expectancy of the son which mirrors pre-SECURE ACT rules.

Additional complications beyond the scope of this paper arise when the QRP owner has not yet reached her Required Beginning Date (RBD) before death. While the full implications of such a complication are not covered within this paper, it must be considered when planning for a client who has not yet reached the year in which she turns 72, the usual (though not the only) Required Beginning Date (“RBD”). [125]

The problem of the loss of beneficial tax treatment when naming the estate is even more pronounced when the intended recipient of the QRP is the spouse of the owner. In that case, while naming the estate (with the spouse taking ownership through the terms of the owner’s will) continues to have the same restrictive distribution requirements. On the other hand, naming the spouse as the Designated Beneficiary has additional positive tax results in addition to the ability to stretch the QRP out for his or her life, should that life expectancy be longer than that of the original QRP owner.[126]This preferential treatment includes the ability for the surviving spouse to roll-over the QRP, if the election to do so is properly and timely made, so that he or she is treated as though he or she were the original owner of the plan.[127] This can allow the spouse to defer the initial distribution from the plan until the later of the year after the year in which the QRP owner dies or the year of the surviving spouse’s RBD if the surviving spouse has not yet reached his or her RBD.[128] This can delay the beginning of the distributions as well as allowing the surviving spouse to elect to use his or her own age to set the life expectancy for the RMDs. Additionally, a surviving spouse (unlike any other Designated Beneficiary) can name his or her own Designated Beneficiaries, since he or she can elect to be treated as though he or she created the QRP rather than simply inheriting the QRP.[129]